Analysis: Brady Photos Are of President Abraham Lincoln’s Funeral

The last few days have seen the publication and republication of news about a Maryland man’s find in the National Archives.

Mr. Paul Taylor of Columbia, Maryland believes that two photos, both labeled “Scene in front of church, ca. 1860 – ca. 1865” in the archives, are in fact forgotten photos of President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral procession.

Partly because I was convalescing from a multi-day illness and needed something light to do, I decided to take another dive into digital (and historical) forensics. To this end, I conducted an independent examination of the two photos.

My analysis strongly confirms that these are, in fact, images of Abraham Lincoln’s New York funeral.

First of the two images. People in front of a church, including a large contingent of soldiers. Click to examine the really large version (in most browsers, you can also right-click, and open the link in a new tab).

First, a note about the era and source of the photos. They came from Mathew Brady, the famous chronicler of the Civil War. Brady is known to have covered Lincoln’s funeral. The specific photographic technology used for these photos was only used during a certain era. It was invented, became current, and then was dropped in favor of newer, better methods. In addition, the National Archives has records on when they acquired the photos. So this gives a general idea of when they were taken.

The era for this technology included the mid 1860s, so the source and general dating of the photos make it immediately possible that they could be of President Lincoln’s funeral.

Location and General Plausibility

A careful comparison of the church in the photos with images of Grace Church, 802 Broadway, New York, makes it clear that Grace Church is the church in the photos.

Grace Church was built well before Lincoln’s death, in 1846-1847. Grace Church was (and is) regarded as an architectural masterpiece. There does not seem to be any other church identical to it. It is unique in the world. These facts establish a clear and definite location for the photos.

Historical records confirm that Lincoln’s funeral procession did in fact pass in front of Grace Church, on the afternoon of April 25, 1865.

It passed from south to north, which is the direction of the moving procession in the second photo.

Military Participation

The presence of well over 100 soldiers, seen clearly in the first photo in full dress uniform including brilliant white gloves, indicates this was an important event with official military participation.

Known images of Lincoln’s New York funeral show soldiers in similar dark-colored uniforms. Some of these are drawings. From a drawing of the funeral at New York City Hall, it is clear that there were multiple styles of uniform worn. This is no doubt due to the participation of different companies and groups of soldiers.

All of this so far is consistent with Lincoln’s funeral, but of course we have nothing definitive yet. There were no doubt other parades which drew military participation as well.

The Time of Year

The photos give up some very good clues as to the time of year. There is a tree with large, light-colored flowers at the lower left, which has bloomed earlier than any other tree visible. The tree in front of the church does not appear to be entirely barren, but it still has little in the way of foliage. (These trees, as with all other details, can be examined in detail by viewing the high-magnification images.)

A flowering tree. The most likely candidate? Probably a saucer magnolia, or perhaps a star magnolia.

At the moment and in lieu of better information, I consider the saucer magnolia to be the most likely candidate for the flowering tree. These are common in New York City. It might also be a star magnolia, but the petals appear too wide. The star magnolia reportedly blooms in April. The saucer magnolia can reportedly bloom as early as March, or as late as May.

Either of these trees is consistent with a date of April 25.

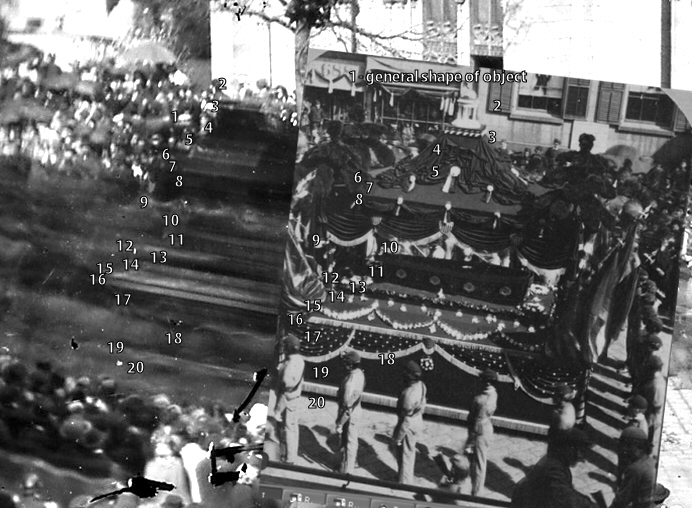

Second image (again, click to super-size). A procession passes. What is the dark blurred object at the left?

Eliminating Some Other Possibilities

The springtime dating of the photo can also be used to rule out certain other possibilities.

For example, I examined the entire list of Union generals killed in action one by one. This ran into the dozens. The only Union general I found killed in action who was from New York City was Stephen H. Weed. He was from Staten Island, not Manhattan, making it unlikely this could have been his funeral. But beyond that: Weed was killed at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Even if Weed had had a procession in Manhattan, this could not have been it, because Weed died well into the summer.

Such a one-by-one consideration of the dozens of Union generals killed in action pretty much rules out the possibility of this having been the funeral of any Union general at all.

And yet, there is extremely good reason to believe this was a funeral. People are dressed in their fine clothes — their Sunday dresses and top hats — but there does not seem to be any air of festivity or celebration.

The Union lost more than 350,000 soldiers in the war. It seems unlikely a funeral for a less important officer could have generated this kind of crowd.

Is it possible this was merely some kind of military parade, or a political event? It doesn’t seem likely. Where are the flags and festivities?

Pace of the Procession

At first glance, it may appear that the procession advanced most of the way across the scene while the shutter was open. This is not the case.

It is easy to identify 11 distinct wavy streaks in the procession, all of the same approximate length. These are approximately 5 feet long, and they tell us how far the procession moved while Brady’s negative was being exposed.

It was a bright, sunny day. A typical portrait (which would likely have been shot in good light indoors) should have taken approximately 15 to 30 seconds with the wet-plate photographic technology Brady’s studio was using at the time.

[Edited: In the original version of this article, I used an estimate of 10 seconds for the photo’s exposure time. Although I qualified that estimate heavily even then, I’m now convinced, as a result of trying to compare exposure times for indoor and outdoor lighting, that this initial estimate was so far off the mark as to simply be useless. Part of the problem is that different lenses would’ve been used for portrait and outdoor photography.

For these reasons, it now seems to me very difficult to get a good estimate of how long the exposures of these photographs were — unless someone can produce some documentation from Brady himself on how long he generally exposed outdoor subjects in direct sunlight. My idea was to try and pin down the pace of the procession and compare that to the historical records. However, that doesn’t seem workable. A relatively small difference in the number of seconds of exposure changes any estimate of the procession’s speed by too much.

Historically, the pace of Lincoln’s funeral procession averaged about 2 miles per hour from City Hall to the Hudson River Train Depot at 10th Avenue & 30th Street. 4 miles, 2 hours. There seems to be some indication that they started out more slowly at the beginning, and then moved more quickly toward the end of the route.

Since I was ultimately unable to produce a good estimate of the pace of the procession from the photographic evidence, there’s really no information here to confirm whether or not the pace matches Lincoln’s funeral. However, there’s also nothing to indicate that the pace doesn’t match that of the Lincoln funeral procession.]

Time of Day

It is possible to get a good idea of what time of day it is, by examining the angle of the shadows in the entranceways of the church. These indicate a time of mid to late afternoon. If a particular event were held in the morning, then this is not it.

Lincoln’s funeral should have passed in front of Grace Church, by my estimation, at approximately 3:30 to 3:40 pm. Once again, the time in the photo is completely consistent with the timing of Lincoln’s procession.

[Note: Since writing this article, further information has emerged on the exact time of day both of Lincoln’s funeral procession, and the Brady photos. While I initially overestimated how much information might be gained about the speed of the procession, it turns out I significantly underestimated what might be learned about the time of day!

First, we should note that I missed the time of the procession in my estimation above, though not by a huge margin.

On April 25, 2014, Mr. Jim Sundman rode the train to New York to take photos of Grace Church on the anniversary of Lincoln’s New York funeral procession.

Mr. Sundman then visually estimated times for the Brady photos, based on a comparison with his own. He wrote to me with the thought that his time estimates for the Brady photos did not appear to match the historical times of Lincoln’s procession.

In terms of the sun’s position in the sky, the 1865 and 2014 dates are directly comparable, because the spring equinox occurred on March 20 of both years. So there’s no significant “skew” due to the equinox being on different dates.

There is, however, another immediate differential: Daylight Saving Time, which did not exist in 1865. After noting that, we embarked upon an extensive investigation into precisely how time was kept in 1865 — no time zones existed, and all time was local in 1865 — and its relation to 2014 time. This investigation quickly became a collaborative effort between Jim Sundman, Paul Taylor, myself, and several other individuals historians and scholars including Center for Civil War Photography President Bob Zeller and Lincoln funeral expert Richard Sloan. Our investigation went so far as to include consultation with an expert at NOAA — the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — in order to confirm some precise astronomical time-keeping details.

When the investigation was complete, it became clear that not only was Mr. Sundman’s time estimate for the Brady photos NOT contradictory to the idea that this was Lincoln’s funeral — his eyeballed estimate of the photograph time, based on the church shadow, was within roughly 5 minutes of the actual time of day that Lincoln’s procession had passed before the church!

It’s important to note that no adjusting of data to fit any desired result took place in this analysis. We faithfully noted Mr. Sundman’s precise original time estimates, to the minute. We then separately determined how to adjust for 1865 time, and made those adjustments. We also worked to determine the best estimates possible, based on the contemporary newspaper accounts, of the moment that Lincoln’s hearse would have been in the position observed. When these processes were complete, the two times came out within roughly 5 minutes of each other.

This can only be described as a “direct hit.”

During this analysis, another significant detail also emerged. Newspaper accounts state that the procession halted at 3 pm to allow the military to depart and make way for the hearse to proceed faster. This time corresponds, again to within less than 5 minutes, with Sundman’s original time estimate for the first photo, the one with soldiers standing in the street. It therefore provides a clear explanation for what is taking place in that photo.

As of spring 2015, a summary of this detailed time analysis had been written up by Mr. Paul Taylor, with a view to publishing it in a historical publication.]

The Crowd and the Weather

The characteristics and behavior of the crowd also give clues. We’ve noted the dress, with many top hats. There were also many umbrellas (which also gives us a clue about the weather and the time of year, which again is consistent with April 25th).

Average daytime high on April 25 in New York City is approximately 62 degrees Fahrenheit, with the possibility of variation one direction or the other. A close examination of the crowd finds no one who can be identified as wearing short sleeves. Pretty much everyone — including all visible children — has a coat or a sweater. The children, in fact, are the people to observe regarding the temperature, because they are the ones most likely to wear short sleeves in warmer weather. The formal nature of the event makes it likely that grown men would wear coats even if the weather were uncomfortably warm. Everything we see here is again consistent with April 25 in NYC.

There are people who have climbed a tree, for a better look at the procession. The tree is tall and difficult to scale. It must’ve taken a lot of skill and effort to get up there.

This does not appear to be normal behavior, even for a big funeral. No, there appears to have been something extraordinarily important going on here.

While there were some other big funerals — the first Union general to be killed in the conflict had 10,000 to 15,000 people show up for his — the size of this crowd, and their dress and behavior, are entirely consistent with this being a photo of President Lincoln’s funeral. This was said to have been the largest event ever to take place in the City of New York. The crowd size in this photo, while it covers only a small portion of one street, appears identical to the crowd size seen in other images of Lincoln’s funeral procession.

The weather also appears to be consistent with the weather during Lincoln’s New York funeral. A contemporary newspaper account from 4:35 pm that afternoon describes “bright sunlight.”

So we now know some things about this event. We know roughly what time of year it took place, what time of day, and to a fair degree, in what weather. We have a good idea what kind of event it was.

And everything we know so far is 100% consistent with it being Lincoln’s funeral.

Soldiers Behind and To the Side

So now let’s get more specific.

The blurred image shows clearly that there were uniformly-dressed persons — soldiers — marching in very regular step behind and to the side of a carriage. This is very similar to the configuration shown in a known photo. Yes, the same basic configuration may have been used for other large military funerals or events, but as discussed, this does not appear to be a festive parade, and there appears to be no other possible major military funeral this could have been.

What about the number of soldiers marching behind the carriage? If there is any problem at all with the Lincoln-funeral theory, it is here. The known photo of Lincoln’s funeral shows, apparently, seven soldiers behind the carriage. Our blurred Brady photo does not seem to show that many. Five perhaps, but probably not seven.

However, the number of soldiers in formation behind the carriage may well have been adjusted. This particular stretch of Broadway looks very, very narrow, and the procession had to have marching room. So I don’t consider this to be a major problem to the idea that we are looking at Lincoln’s funeral.

In fact, it’s very difficult to examine any event in this detail and not turn up something that deviates a bit what from you might expect.

I find it rather remarkable that this is the first thing we’ve found that seems to deviate even slightly from what we would expect to have seen at Lincoln’s funeral.

Graphic Comparison of the Blurred Carriage With Lincoln’s Actual Hearse

And now, finally, we arrive at a place where the rubber really meets the road.

First, we should note that there was not a single template for a horse-drawn hearse. These, of course, were large affairs. Lincoln’s casket was loaded on the train, but the hearse used in New York City was left behind.

Photos of the Philadelphia hearse show that the only common characteristics between that one and the one used in New York were that each had a canopy and decorations of draperies and fringe. Other than that, the style and design were entirely different.

So the question is: Is the blurred carriage in the Brady photo Lincoln’s New York hearse?

We can do a careful and direct graphic comparison, placing the blurred image of Brady’s photo side by side with the known image. When we do this, a strong correlation is immediately obvious.

More specifically, we can make points of comparison between the blurred image, and the known one. I have listed 20 such points of comparison, and will briefly comment on each. (Again, right-click the image and open separately for a larger view.)

1. The general shape of the two objects is the same.

2. A white blur is visible corresponding to the top ornament. This is more visible at bottom than at top, although in one adjustment of the photo I was able to see it at top as well.

3. The white dots appear visible as a white streak.

4. This is a dark area in both photos.

5. White ornaments visible as a blur.

6. A sloped, lighter-colored area.

7. Ends in an edge with light ornaments. These are visible as a streak.

8. Darker area below the edge.

9. Light area caused by fringe. This is more blurred because the fringe is sloped.

10. Top of Lincoln’s casket. In both photos, the top part of this is in shadow, the lower (nearer) part less so.

11. Side of Lincoln’s casket.

12. The platform on which it rests, lighter in color. There is a streak of white at the front because of a large white decoration.

13. A dark vertical edge a couple of inches in height.

14. A blur of small white decorations in a row.

15. Broader blur of draping white decorations.

16. Row of fringe matches, in size and position.

17. Darker area below the fringe.

18. Blur of draping fringe and marching soldiers in front of it.

19. Bottom fringe. Again, exactly the right size and position. And the stronger solid-white color of the top line where the fringe is sewn is clearly visible even in the blurred image.

20. A shadow — of the same size — is clearly visible below the carriage in both photos.

Although I have not labeled them, it is possible also to distinguish dark blurs corresponding to the dark plumes, the dark flags, and the dark horses.

In short, the blurred image contains visible features corresponding directly and precisely to every single visible feature of Lincoln’s hearse.

And there is no feature that does not match the characteristics of Lincoln’s hearse.

The only rational conclusion is that if this is not Lincoln’s hearse, then it is identical to it in every important way. It seems to have had even the same dark plumes known to have decorated Lincoln’s hearse.

This leaves us with only one major question remaining.

Was Lincoln’s Hearse a Standard One, or Was It Unique?

We now know that the image contains a hearse, and that this hearse was identical to President Lincoln’s in every identifiable feature — more than 20 of them.

But if this was a standard hearse used for many different funerals, then this funeral could be for someone besides President Lincoln.

But the New York hearse was not a standard issue. It was specially created for Lincoln’s funeral. The City paid undertaker Peter Relyea $9,000 to build it, and it was to be used for this one funeral. It was unique.

The City of New York did continue to use the hearse for several years afterward — in re-enactments of the Presidential funeral conducted during their annual 4th of July parades.

Since these were apparently the only occasions on which the hearse was used, that narrows this event down into one of two possibilities: Either it was President Lincoln’s actual funeral, or it was a re-enactment.

Which it was is answered easily by the tree which in bloom, and all the others which are still nearly bare. This was not the 4th of July.

Conclusion

We have now examined the Brady image in detail. We’ve learned a number of things about it. We’ve examined the time of year, the time of day, and various other factors.

Everything we found is consistent with the theory that this is a photo of President Lincoln’s funeral. We’ve pretty well ruled out other kinds of events, even funerals of important military leaders.

We’ve found that the blurred carriage in the photo, when compared side by side with a known photo, matches President Lincoln’s unique funeral hearse in every particular — more than 20 of them in all. We’ve found that not only was Lincoln’s hearse unique; it was only used for this one funeral, and for its 4th of July re-enactments. And we have seen that this can not have been a 4th of July re-enactment.

All of this leads us to an inescapable conclusion.

This is indeed a photo of President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral procession.

The dark blur in the photo is President Lincoln’s hearse, with his casket on board.

And the photo was taken as Lincoln’s casket passed in front of Grace Church,on Broadway in New York City, in the mid-afternoon of Tuesday, April 25, 1865.

[A final note: The conclusion above came from my initial investigation. As clear as the conclusion was at that time, it has since been still further confirmed by the collaborative shadow analysis, which both explains the first photograph and clearly places the time of day for both photographs within minutes of the historical times expected.

While it is very sensibly against the rules of the National Archives and Records Administration to change the historically assigned titles of items in the National Archives — and in this case the titles date from the 1800s — they have now added notes to the cataloging for both photos. These notes reflect the clear evidence, and the consensus among multiple researchers, historians and experts, that these two Mathew Brady photographs are images of President Lincoln’s funeral procession, taken the afternoon of April 25, 1865.]